CIHR Institute of Health Services and Policy Research Strategic Plan 2015‑19

Health system transformation through research innovation

Table of Contents

- Scientific Director’s Message

- Our Context: Healthcare in Canada

- Our Story: Health Services and Policy Research in Canada

- Our Background: The Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- A Common Vision and Strategic Direction for Health Services and Policy Research: Building a Canadian Alliance

- Our Strategy: The Next Five Years

- Strategic Priority 1: The Creation of Learning Health Systems and the Next Generation of Researchers with the Skills to Partner in Health System Learning and Transformation

- Strategic Priority 2: eHealth

- Strategic Priority 3: Healthy Aging in the Community

- Strategic Priority 4: Health System Financing, Funding, and Sustainability

- Our Outlook: Concluding Remarks

- Acknowledgements

- References

List of Figures

- Figure 1: The History of Health Services and Policy Research in Canada

- Figure 2: Total Funding Awarded Grant Applications for Health Services and Policy Research in the Open and Strategic by Fiscal Year (2001‑2011)

- Figure 3: The Number of CIHR Grant Applications by Pillar and Year

- Figure 4: The Number of Health Services and Policy Scientists (Nominated Principal Applicants on CIHR Grant Applications) by Year

- Figure 5: CIHR Signature Initiatives and Health Services and Policy Research

- Figure 6: The Future Evolution of Health Services and Policy Research in Canada

- Figure 7: Total Health Services and Policy Research Investment in Canada (2007‑2011)

- Figure 8: Leading Funders of Health Services and Policy Research in Canada

- Figure 9: Total Health Services and Policy Research Investment by Research Theme (2007‑2011)

- Figure 10: Health Services and Policy Research Priority Areas

- Figure 11: Health Services and Policy Research Priorities and Foundational Strategic Directions

- Figure 12: International Comparisons in Healthcare System Performance: the Commonwealth Fund Survey

- Figure 13: Historical and Future Expected Age and Sex Distribution in the Canadian Population

- Figure 14: The Prevalence of Multi-morbidity by Age

List of Appendices

- Appendix 1: Strategic Planning Methodology

- Appendix 2: Organizations Partnered on IHSPR’s Pan-Canadian Vision & Strategy Initiative

- Appendix 3: Partner Organizations for Evidence-Informed Healthcare Renewal (EIHR)

- Appendix 4: Roundtable Organizations

1. Scientific Director’s Message

The CIHR Institute of Health Services and Policy Research (IHSPR) has set out an ambitious direction for the next five years. We aim to build the scientific leadership for learning health systems in Canada, tap into the transformative potential of eHealth for Canadian healthcare, find a better system to support aging in the community, and provide research intelligence on the question of how to finance and fund the health system of the future.

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Health Research Roadmap II: Capturing Innovation to Produce Better Health and Health Care for Canadians (Roadmap II) provided us with the foundation for our vision and strategy, with the formation of the Canadian Health Services and Policy Research Alliance (CHSPRA) as the enabling network to tackle the real-world challenge of health system transformation, and learn from the natural experiments that occur in the 13 provincial and territorial healthcare systems in Canada.

CIHR’s Strategy for Patient Oriented Research (SPOR), one of CIHR’s Roadmap Signature Initiatives, is considered throughout the strategic plan as a complimentary CIHR investment. As SPOR’s development continues, IHSPR will leverage SPOR investments, and ensure IHSPR activities remain complimentary and synergistic to SPOR. As IHSPR operationalizes our plan, we will also strive to emphasize consideration of CIHR’s sex and gender directions, language policies, inclusion of official language minority communities and indigenous populations, as well as other key populations. Where appropriate, IHSPR will encourage inclusion of official language considerations and of English and French speaking Canadians, including those living in minority communities, in health research design and conduct to improve health outcomes.

IHSPR owes the wisdom of its directions to a range of stakeholders: CHSPRA and its inaugural 33 member organizations, our Institute Advisory Board that guides our priority areas, and the talented and professional staff of CIHR and its virtual Institutes who help actualize our dreams for the future of health research in Canada.

Robyn Tamblyn

Scientific Director

Institute of Health Services and Policy and Research

2. Our Context: Healthcare in Canada

Healthcare spending in Canada is growing at an unsustainable rate, exceeding $210 billion in 2013Reference 1. Canada invests $5446.50Reference 2 per person on healthcare, considerably more than other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries but ranks second to last in key healthcare areas such as access, safety, and quality of careReference 3. Key cost drivers include provider compensation, utilization of services, and the emergence of new devices and technologiesReference 1. Spending on healthcare delivery accounts for close to 50% of total budgets in a number of provinces and territories, crowding out spending on other important priorities like education and social services.

These financial pressures provide impetus for transformational change, and an increasing pull for cutting edge research that can pioneer innovations in health system delivery that can lower costs, improve patient experience, quality of care, and the health of Canadians. Canada’s healthcare “system” provides a unique environment for health services and policy research in that it comprises over 13 distinct delivery systems – one in each of the ten provinces and three territories, as well as federal systems for certain populations (e.g. First Nations and Inuit peoples, the military and prison populations). This rich arena of innovation and experimentation generates valuable opportunities for natural experiments and cross-jurisdictional comparative analyses that shed insight into the successful features of different service delivery models and areas for growth and improvement.

3. Our Story: Health Services and Policy Research in Canada

Health services and policy research (HSPR) is the field of scientific investigation that generates evidence in how to invest in programs, services and technologies that maximize health and health system outcomes. Multiple disciplines, professions, and methodologies are harnessed to creatively address health system challenges and answer high-priority questions.

These questions cover a spectrum of topics such as whether pay-for-performance works; how to remunerate delivery organizations and providers to incentivize better outcomes; whether integrated delivery models improve patient experience and outcomes; how to provide long-term care financing for a rapidly aging population; and how to implement eHealth innovations to improve access to mental health services.

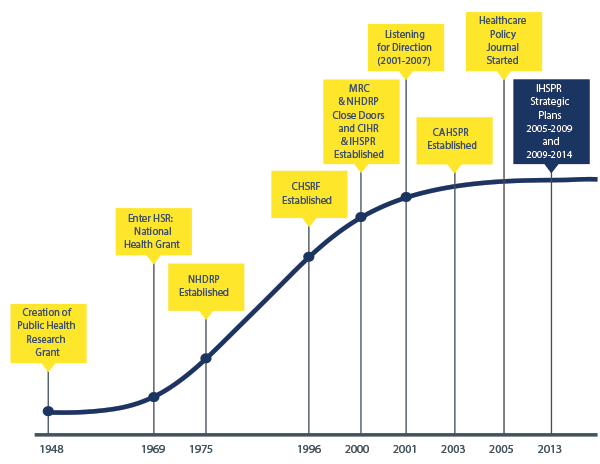

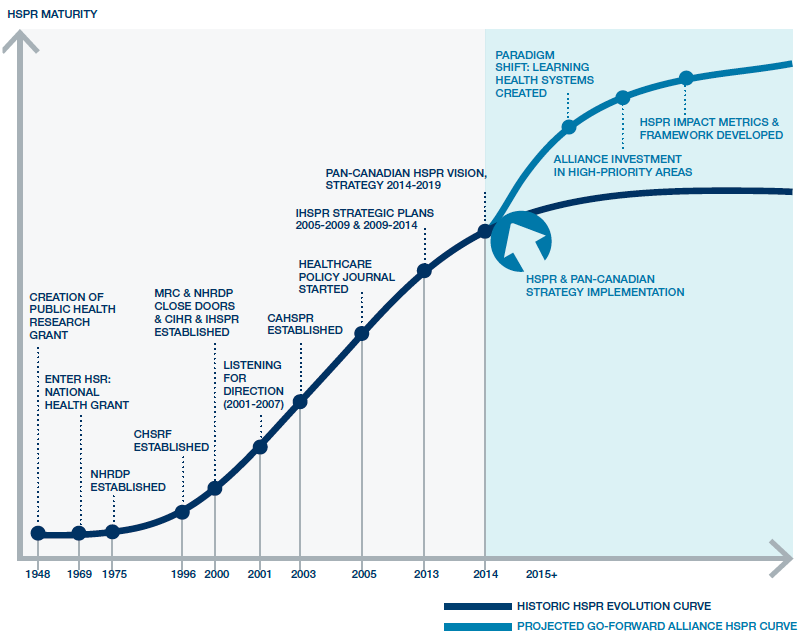

The key requirements for responsive, world-class research are a skilled community of multidisciplinary researchers, accessible platforms and infrastructure, engaged knowledge users committed to evidence-informed policy- and decision-making, and sustainable funding programs. Canada’s health services and policy research enterprise has evolved significantly over the past 20 years (Figure 1) and has witnessed growth in many areas, including funding and programs to support innovative research.

Figure 1: The History of Health Services and Policy Research in Canada

Figure 1 long description

| Year | Event in HSP Research |

|---|---|

| 1948 | Creation of Public Health Research Grant |

| 1969 | Enter HSR: National Health Grant |

| 1975 | NHDRP Established |

| 1996 | CHSRF Established |

| 2000 | MRC & NHDRP Close Doors and CIHR-IHSPR Established |

| 2001 | Listening for Direction (2001‑2007) |

| 2003 | CAHSPR Established |

| 2005 | Healthcare Policy Journal Started |

| 2013 | IHSPR Strategic Plans 2005‑2009 & 2009‑2014 |

4. Our Background: The Canadian Institutes of Health Research

One of the seminal achievements of the health services and policy research enterprise was the formation of IHSPR as one of 13 Institutes within CIHR. Established in 2000, CIHR’s mandate was to create new scientific knowledge and to catalyze its translation into improved health, more effective health services and products, and a strengthened Canadian healthcare system.

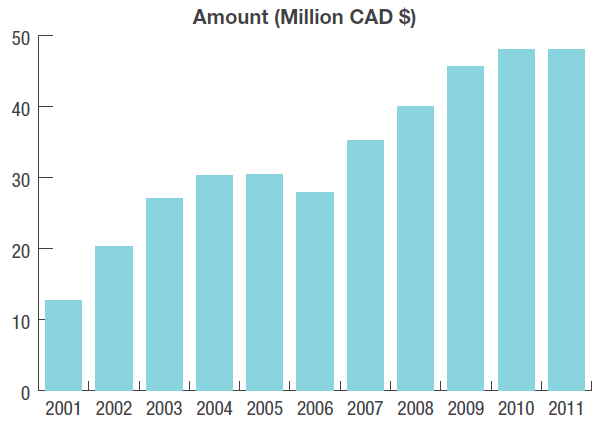

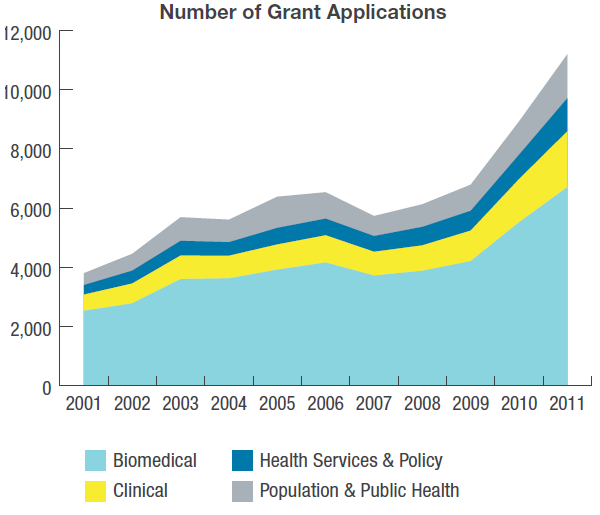

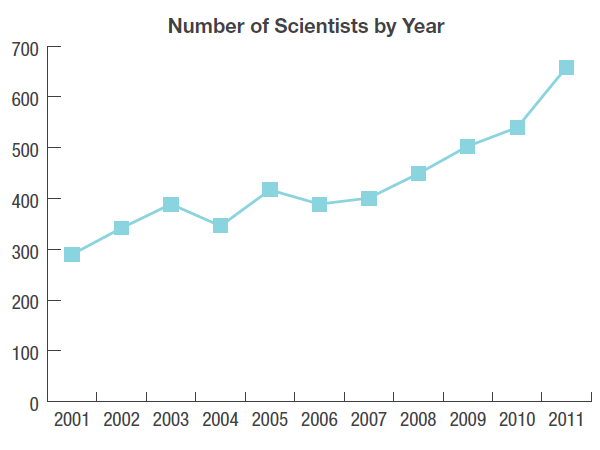

In the first decade, based on application data to CIHR, health services and policy research grew under this new organization. Between 2001 and 2011, funding for grant applications for health services and policy research increased from $12.6 to 48 million (Figure 2), the annual number of applications increased from 327 to 1,137 (Figure 3), and the number of principal nominated applicants increased from 290 to 659 (Figure 4).

Figure 2: Total Funding Awarded Grant Applications for Health Services and Policy Research in the Open and Strategic by Fiscal Year (2001‑2011)*

Figure 2 long description

| Year | Amount (Million CAD $) |

|---|---|

| 2001 | 12.66 |

| 2002 | 20.30 |

| 2003 | 26.97 |

| 2004 | 30.30 |

| 2005 | 30.40 |

| 2006 | 27.82 |

| 2007 | 35.16 |

| 2008 | 40.01 |

| 2009 | 45.66 |

| 2010 | 47.96 |

| 2011 | 48.04 |

* The amount in each fiscal year represents the first year expenditure for new grants awarded as well as subsequent years of funding for grants awarded in previous years. As data were only available for new grants starting in the 2001‑02 fiscal year (not amounts awarded through the prior awards at MRC and NHRDP), the sum is artificially lower in the 2001‑02 and 2002‑03 fiscal years.

Figure 3: The Number of CIHR Grant Applications by Pillar and Year

Figure 3 long description

| 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biomedical | 2526 | 2778 | 3599 | 3623 | 3917 | 4159 | 3716 | 3879 | 4206 | 5519 | 6707 |

| Clinical | 545 | 668 | 791 | 762 | 849 | 917 | 803 | 857 | 1028 | 1454 | 1884 |

| Health Services &Policy | 327 | 438 | 502 | 461 | 564 | 566 | 534 | 628 | 672 | 830 | 1125 |

| Population and Public Health | 400 | 569 | 798 | 762 | 1054 | 893 | 678 | 764 | 884 | 1126 | 1486 |

Figure 4: The Number of Health Services and Policy Scientists (Nominated Principal Applicants on CIHR Grant Applications) by Year

Figure 4 long description

| Year | Number of Scientists by Year |

|---|---|

| 2001 | 290 |

| 2002 | 342 |

| 2003 | 389 |

| 2004 | 346 |

| 2005 | 417 |

| 2006 | 389 |

| 2007 | 401 |

| 2008 | 449 |

| 2009 | 503 |

| 2010 | 540 |

| 2011 | 659 |

Moreover, as a champion of one of CIHR’s four major pillars (health systems and services), IHSPR leads CIHR-wide initiatives that engage multiple Institutes such as the eHealth Innovations Initiative and the Signature Initiatives in Community-based Primary Healthcare (CBPHC), the SPOR Pan-Canadian Network in Primary and Integrated Health Care Innovations (PIHCI), and Evidence-Informed Healthcare Renewal (EIHR) (Figure 5). IHSPR also works closely with our sister Institutes to integrate health services and policy research within their strategic funding programs and within other CIHR Signature Initiatives (e.g. Personalized Medicine and Pathways to Health Equity).

Figure 5: CIHR Signature Initiatives and Health Services and Policy Research

Community Based Primary Health Care (CBPHC)

Supports Highly Innovative Approaches to improving the delivery of high quality and appropriate CBHC.

CIHR Investment: 49M

Partners investment: 5M

Number of grants: 58

SPOR: Pan Canadian Network in Primary and Integrated Health Care Innovations

Supports evidences for informed transformation and delivery of integrated healthcare to improve health and health outcomes for individuals with or at risk of developing complex health needs.

CIHR Investment: 13.5M

Partners investment: 13.5M

Number of grants: 11

Evidence Informed Healthcare Renewal (EIHR)

Generates timely and high quality evidence on how to best finance, sustain, and govern healthcare systems.

CIHR Investment: 65M

Partners investment: 942K

Number of grants: 83

Personalized Medicine and Pathway to Health Equity

Personalized Medicine

CIHR Investment: 85M

Partners investment: 156M

Number of grants: 58

Pathways to Health Equity

CIHR Investment: 26.5M

Partners investment: 100K

Number of grants: 5

However, health services and policy research continues to represent a very small proportion of the strategic and open operating grant funds awarded by CIHR: 3.2% of overall funding in 2001‑02 and 6.3% of all applications funded in 2011‑12. A paradigm shift is needed if health services and policy research is to drive health system transformation. We will need to create alignment and synergy among health services research funders, researchers, and end-users, build a vision of what we want to accomplish, establish what we need to do, and build a strategy to get there.

The Canadian Cancer Research Alliance has successfully tackled a similar challengeReference 4, and created a model that could be used to achieve transformation in HSPR research. We used this model to establish the Canadian Health Services and Policy Research Alliance (CHSPRA). The aim of CHSPRA is to foster collaboration, coordination, and strategic investment among health services and policy research organizations in Canada, to accelerate scientific innovation and discovery, optimize the impact of research on health and health system outcomes, and strengthen the research enterprise. CHSPRA will provide the basis for propelling the health services and policy research community into the next phase of maturity – a phase in which IHSPR will play a foundational and leadership role (Figure 6).

Figure 6: The Future Evolution of Health Services and Policy Research in Canada

Figure 6 long description

| Year | Number of Scientists by Year |

|---|---|

| 1948 | Creation of Public Health Research Grant |

| 1969 | Enter HSR: National Health Grant |

| 1975 | NHDRP Established |

| 1996 | CHSRF Established |

| 2000 | MRC & NHDRP Close Doors and CIHR & IHSPR are Established |

| 2001 | Listening for Direction (2001‑2007) |

| 2003 | CAHSPR Established |

| 2005 | Healthcare Policy Journal Started |

| 2013 | IHSPR Strategic Plan (2005‑2009 & 2009‑2014) |

| 2014 | Pan-Canadian Vision and Strategy 2014‑2019 |

| 2015 + |

|

5. A Common Vision and Strategic Direction for Health Services and Policy Research: Building a Canadian Alliance

The creation of CHSPRA is the result of a three-step process initiated and led by IHSPR.

First: Mapping our Assets

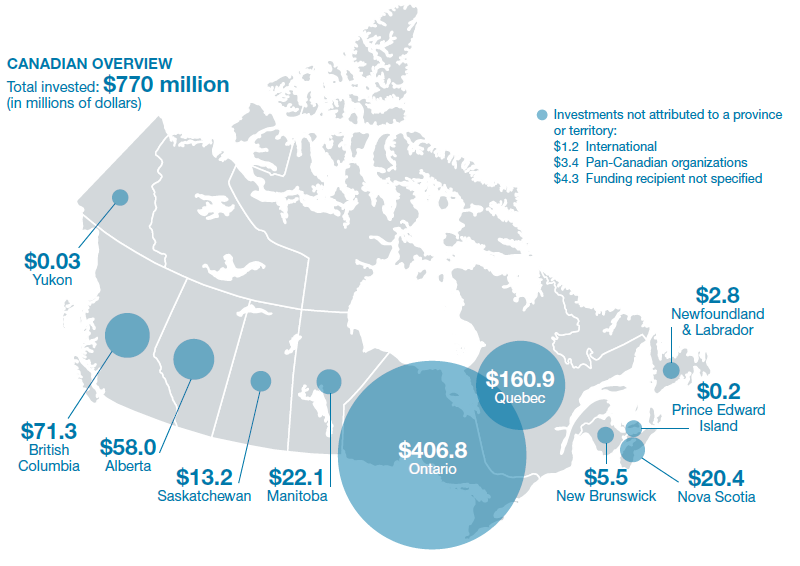

IHSPR collaborated with provincial health research funders and health charities to create an asset map of the collective investments in health services and policy research made by Canadian organizations. The map identifies the source as well as geographical location of the investments over a five year period (2007‑2012). Twenty-seven organizations contributed data to the map.

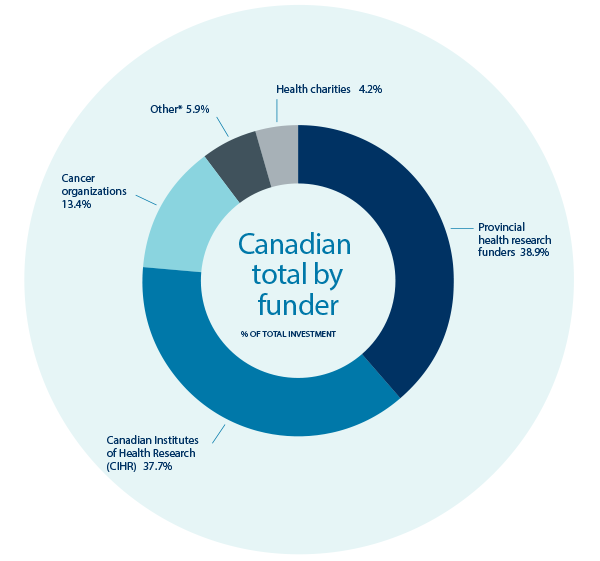

We found that $770 million had been spent in health services and policy research over the five year period (Figure 7). This money was awarded to 225 organizations active in Canada’s HSPR enterprise. Of interest, CIHR accounted for only 37.7% of health services research funding, opening opportunities to increase synergy by partnering on common priorities with provincial health research funders, health charities, and other funders (Figure 8).

Figure 7: Total Health Services and Policy Research Investment in Canada (2007‑2011)

Figure 7 long description

| Province or Territory | Research Investment ($ Million) |

|---|---|

| Canadian overview – Total invested | 770 |

| Yukon | 0.03 |

| British Columbia | 71.3 |

| Alberta | 58.0 |

| Saskatchewan | 13.2 |

| Manitoba | 22.1 |

| Ontario | 406.8 |

| Quebec | 160.9 |

| New Brunswick | 5.5 |

| Nova Scotia | 20.4 |

| Prince Edward Island | 0.2 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 2.8 |

| Total Investment | 770 |

Investments not attributed to a province or territory:

- $1.2 International

- $3.4 Pan-Canadian organizations

- $4.3 Funding recipient not specified

Figure 8: Leading Funders of Health Services and Policy Research in Canada

Figure 8 long description

| Funder | Contribution (%) |

|---|---|

| Health Charities | 4.2 |

| Other * | 5.9 |

| Cancer Organizations | 13.4 |

| Canadian Institutes of Health Research | 37.7 |

| Provincial Health Research Funders | 38.9 |

*“Other” includes Canada Foundation for Innovation, Canada Research Chairs, Canadian Foundation for Healthcare improvement and the British Columbia Ministry of Health.

Second: Creating a Common Vision and Strategic Direction

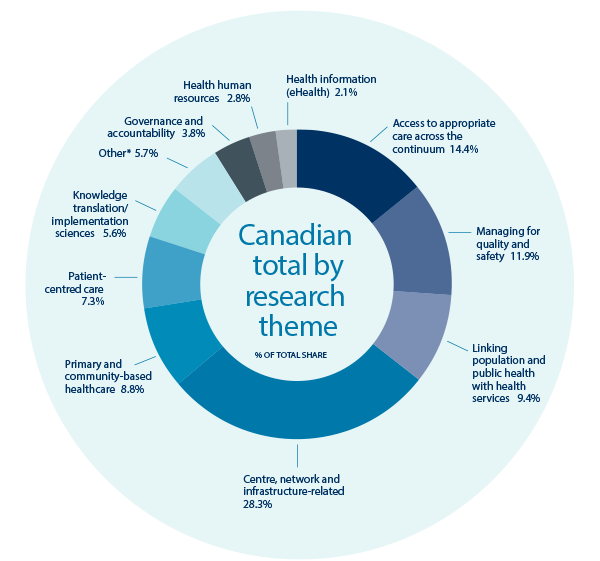

To build a common vision and strategic direction for the future, we first evaluated what had been funded in the field of health services and policy research. The top-funded themes included: access to appropriate care across the continuum (14.4%), managing for quality and safety (11.9%), and linking population and public health with health services (9.4%). Very little investment had been made in healthcare financing and funding (1.6%) and change management / scaling up innovation (0.3%), even though they were hot topics identified by many policy think tanksFootnote 5-8.

Figure 9: Total Health Services and Policy Research Investment by Research Theme (2007-2011)

Figure 9 long description

| Research Theme | HSPR Investment (%) |

|---|---|

| Health Information | 2.1 |

| Health Human Resources | 2.8 |

| Governance and Accountability | 3.8 |

| Knowledge Translation | 5.6 |

| Other* | 5.7 |

| Patient-centered Care | 7.3 |

| Primary and Community-based Care | 8.8 |

| Linking Population and Public Health with Health Services | 9.4 |

| Managing for Quality and Safety | 11.9 |

| Access to Appropriate Care Across the Continuum | 14.4 |

| Centre, Network and Infrastructure-related | 28.3 |

*Data on funding for centres or networks was classified as ‘Unclassified Health Services and Policy Research’

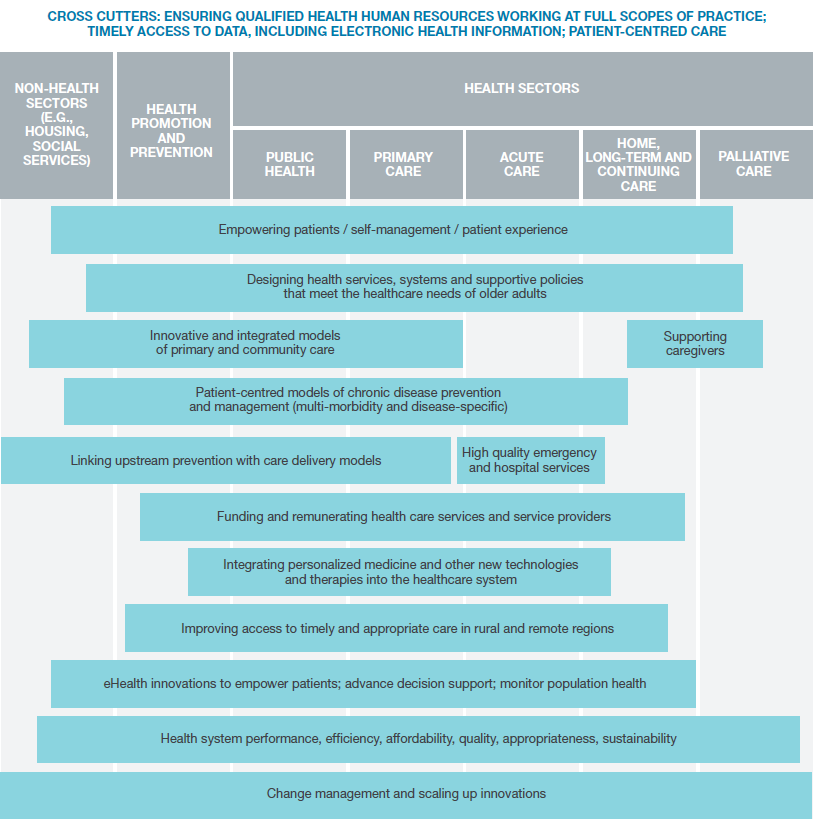

The second step involved using these themes, as well as others identified by CIHR through their environmental scan, for SPOR investment priorities, and consulting our community about the priorities and directions for future investment in health services and policy research in Canada (Figure 10).

To gain broad input, we conducted a web-based survey of Canadian researchers (over 400 responses), consulted more than 55 regional informants including researchers and policy makers, held a Café Scientifique for the general public (117 participants), and solicited input from international leaders through a panel at the annual meeting of the Canadian Association for Health Services and Policy Research (CAHSPR). We also convened a national Priorities Forum of over 100 funders, policy and decision-makers, researchers, and end-users in April 2014 to deliberate on the findings and set a vision and direction for the next 5 years. The Forum participants identified seven foundational strategic directions and five priorities for investment (Figure 11).

Figure 10: Health Services and Policy Research Priority Areas

Figure 10 long description

Cross cutters: Ensuring qualified health human resources working at full scopes of practice; timely access to data, including electronic health information; patient-centred care

Empowering patients/self-management/patient experience: Non-Health sectors (e.g., housing, social services); Health promotion and prevention; public health; primary care; acute care; home, long-term and continuing care; palliative care

Designing health services, systems and supportive policies that meet the healthcare needs of older adults: Non-health sectors (e.g., housing, social services; health promotion and prevention; public health; primary care; acute care; home, long-term and continuing care; palliative care

Innovative and integrated models of primary and community care: Non-health sectors (e.g., housing, social services); health promotion and prevention; public health; primary care

Supporting caregivers: home, long-term and continuing care; palliative care

Patient-centred models of chronic disease prevention and management (multi-morbidity and disease-specific): non-health sectors (e.g., housing, social services); health promotion and prevention; public health; primary care; acute care; home, long-term and continuing care

Linking upstream prevention with care delivery models: Non-health sectors (e.g., housing, social services; health promotion and prevention; public health; primary care

High quality emergency and hospital services: primary care; acute care; home, long-term and continuing care

Funding and remunerating healthcare services and service providers: Health promotion and prevention; public health; primary care; acute care; home, long-term and continuing care

Integrating personalized medicine and other new technologies and therapies into the healthcare system: health promotion and prevention; public health; primary care; acute care; home, long-term and continuing care

Improving access to timely and appropriate care in rural and remote regions: health promotion and prevention; public health; primary care; acute care; home, long-term and continuing care

eHealth innovations to empower patients; advance decision support; monitor population health: Non-health sectors (e.g., housing, social services)health promotion and prevention; public health; primary care; acute care; home, long-term and continuing care

Health system performance, efficiency, affordability, quality, appropriateness, sustainability: Non-Health sectors (e.g., housing, social services); Health promotion and prevention; public health; primary care; acute care; home, long-term and continuing care; palliative care

Change management and scaling up innovations: Non-Health sectors (e.g., housing, social services); Health promotion and prevention; public health; primary care; acute care; home, long-term and continuing care; palliative care

There was immediate interest in working collectively on two strategic directions where resources were already available and being used to address them: 1) measuring HSPR impact; and 2) accelerating the creation of a cadre of scientists that could work within the context of a learning health system.

Figure 11: Health Services and Policy Research Priorities and Foundational Strategic Directions

Figure 11 long description

Foundational Strategic Directions

- Fund relevant research in priority areas

- Create learning health systems

- Foster research and system innovation

- Accelerate the formation of a skilled cadre of health services and policy researchers

- Measure HSPR Impact

- Enable timely access to data and promote smart analytics

- Align academic and system incentives

- Context, change management and scaling up innovation in complex systems

- Innovation in integrated service delivery models to meet evolving health needs of Canadians

- Healthy aging in the community

- Health system performance and value-based funding models

- eHealth and other innovations that improve person-centred, efficient, quality care

Third: Creating the Canadian Health Services and Policy Research Alliance

The Forum resulted in the nomination of an interim executive. The executive is establishing the mandate, governance, and membership of CHSPRA, convening the first two working groups to address research impact and training, and setting up the first annual meeting of members to set priorities for collective investment. To date, many major Canadian health services and policy funding organizations have joined, and the two working groups are underway.

6. Our Strategy: The Next Five Years

IHSPR’s new five-year strategy is purposefully aligned with the pan-Canadian Vision and Strategy for Health Services and Policy ResearchReference 9. Both envision a future where research intelligence drives health system transformation that improves health and health system outcomes for Canadians. Both see partnerships and collaboration as key ingredients to success. Our strategy builds on IHSPR’s track record of research excellence, catalyzing innovative programs and initiatives, and partnering to achieve greater impact. IHSPR’s Institute Advisory Board reviewed the seven pan-Canadian strategic directions and five research priority areas and selected those that IHSPR was well positioned to advance based on an assessment of: 1) gaps and strengths; 2) potential for international leadership; 3) potential for partnering; 4) alignment with CIHR's Roadmap IIReference 10 and synergies with SPOR; and 5) opportunities for inter-Institute collaboration.

The board selected four complimentary priorities where innovation and new evidence is needed to support successful health system transformation and sustainability to meet the needs of an aging society.

- The Creation of Learning Health Systems and the Next Generation of Researchers with the Skills to Partner in Health System Learning and Transformation

- eHealth

- Healthy Aging in the Community

- Health System Financing, Funding, and Sustainability

Strategic Priority 1: The Creation of Learning Health Systems and the Next Generation of Researchers with the Skills to Partner in Health System Learning and Transformation

Each day, millions of Canadians are seen within the healthcare system, and a trillion bits of information are generated. Increasingly the day-to-day use of health and social services are recorded digitally at the point of care. This information could be harnessed to understand the comparative effectiveness of different treatments, the causes of potentially avoidable adverse events, unnecessary costs, missed opportunities for prevention, and to capture the collective wisdom on how to improve patient experience. However, for the most part, we have not used this information to produce knowledge on how we could do betterReference 11. A major initiative that is gaining momentum in the US is to create “learning health systems”, accountable healthcare organizations that use their data in an intelligent fashion to guide how they can improve care in a dynamic wayReference 12. The learning health system emphasizes collaboration across all health borders to drive an efficient and effective systemReference 13-15.

The Gap: There are many challenges that will need to be addressed to move from the health system of today to a learning system of tomorrow. However, a fundamental requirement for success is capable scientific, clinical and policy leadership that will nurture the ability of a health system to experiment with innovation, learn from failure, and scale up success. The skill sets required of scientists within learning health systems are different from those acquired in classic training. They need to be able to partner with clinical and policy leadership to identify relevant priorities for research, develop new methods for rapid scientific investigation using point of care patient experience and digital health and social data, collaborate on the most effective use of emerging knowledge for clinical and policy decisions, and implement and evaluate innovative solutions.

The Objective: To train and fund a new generation of scientists who can provide scientific leadership in learning health systems.

Potential for International Leadership: Canadian scientists already play an international leadership role in knowledge translation, particularly integrated knowledge translationReference 16,17. CIHR pioneered successful partnership programs between decision-makers and researchers (e.g. Partnerships for Health System Improvement, Expedited Knowledge Synthesis, Policy Rounds, Community-Based Primary Health Care teams) creating a culture where partnership models are “the new norm” for health services and policy research. The opportunity for international leadership in learning health systems will be accelerated by SPOR by both providing a model for sustained decision-maker - researcher relationships and a platform through SUPPORT Units to access health and social data.

Alignment with Roadmap II and Synergies with SPOR: A learning health system creates the platform to mobilize research for transformation and impact, particularly in improving the patient experience and outcomes, and quality of life for persons with chronic conditions. Both are priorities for CIHR’s Roadmap II. Focusing on the next generation of scientific leadership for the learning health system also fills an important niche for the SPOR Network on Primary and Integrated Health Care Innovations. This national network links the embryonic learning health system networks, funded in each provincial and territorial jurisdiction, through the common goal of improving the outcomes and experience for patients with complex needs.

CIHR’s Roadmap II also prioritizes “building a solid foundation for the future”, centred on providing students and trainees with the right mix of expertise and skills to succeed in the health-related academic and/or professional careers of the future. IHSPR will engage in the development of a broad CIHR National Framework for Excellence in Health Research Training and resulting CIHR Strategic Action Plan on Training. IHSPR will share the perspective of the HSPR community, as well as ensure IHSPR activities are aligned with the training directions in the CIHR National Framework and are supportive of the resulting CIHR Action Plan on Training.

Potential for Partnering: The creation of a new generation of learning health system scientists spans the spectrum of front-line clinician-researchers to scientists within regional health authorities, quality councils, policy think tanks, and consulting firms. We expect that these organizations will fund or co-fund graduate students, postdoctoral fellows, and career scientists using models for embedded health services research that have been shown to be effective by MITACS, Quebec Chercheurs Cliniciens, and more recently, AcademyHealth in the US.

Opportunity for Inter-institutional Collaboration: Five CIHR Institutes are currently collaborating on the creation of the first national learning health system through SPOR’s PIHCI network [i.e. Institute of Health Services and Policy Research (IHSPR), Institute of Population and Public Health (IPPH), Institute of Aging (IA), Institute of Human Development, Child and Youth Health (IHDCYH) and Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes (INMD).

Expected Impact: In five years we will have created a new cadre of health system scientists. This group will have developed methods of using point-of-care digital data to address priority policy and practice questions in a timely way through both experimental and observational approaches. There will be a corresponding increase in the adoption of new innovations and disinvestment in suboptimal models of care and interventions.

Strategic Priority 2: eHealth

In the upcoming decade, digital platforms will be the backbone of a strategic revolution in the way health services are provided, affecting both healthcare providers and patientsReference 18. eHealth innovations are appearing in almost all areas of healthcare delivery, from prevention, diagnosis, acute through to long-term care, and population health surveillance. There is increasing evidence showing its contribution to efficiency (e.g. reductions in wait times, increased speed of referrals and decision-making), effectiveness (e.g. tele-health clinics for dermatology and psychiatric assessment and counseling), patient education and empowerment (e.g. health experience portals), and safety (e.g. prescription drug dispensing)Reference 19.

The emerging potential of eHealth and its impact on health research is recognized worldwide with many funding agencies placing it in the top five priorities for future investmentReference 20.

The Gap: Canada is lagging behind in efforts to take full advantage of the global trends in digitization that can transform this innovative knowledge into real benefits for patients and for healthcare systemsReference 21. Analysis of the problems in Canada have identified challenges on all sidesReference 22 that limit the development of practical solutions and the adoption of proven eHealth interventions across clinical, administrative and policy settings. Important limitations include: the limited investment in formal evaluation of new technologies (particularly comparative clinical benefit), effectiveness, and comparative cost analysis; limited alignment between Information & Communication Technology (ICT) developments and those working to address significant health problems; and the lack of access for ICT companies to healthcare settings where their products and solutions can be tested in real-world contexts with patients and healthcare providers. eHealth innovations of the future will need to be integrated into client-focused solutions that can change outcomes of care, by improving access, safety, quality and equity, at the same or lower cost.

The Objective: To develop, integrate and evaluate eHealth innovations that will improve the effectiveness and efficiency of patient and population-centred care; and to increase Canada’s competitive position in the health-related ICT industry to support continuing innovation in Canadian healthcare.

Potential for International Leadership: For Canada to leapfrog ahead in eHealth, we will need to successfully create eHealth innovation communities that partner industry with the health system to co-innovate the next generation of value-added solutions. The eHealth Innovation Partnership Program (launched in October, 2014) was designed to create industry-partnered eHealth innovation communities and to start aligning federal and provincial economic development investments in small and medium sized industries with investments in healthcare and research to foster both national and international opportunities. There is relatively recent growth in the number of ‘innovation incubator’ type facilities such as MaRS in Toronto, ON, and Innovation Boulevard in Surrey, B.C. that are a proof of concept of the capacity in Canada to create the winning conditions for international leadership.

We will also need to change the approach used to procure new technologies in healthcare from lowest cost to best evidence-based value selection, remove barriers to adoption such as non-value-based funding models, and create international pathways for innovation exchange and commercialization. Both provincial and federal innovation committee reports support these changes in approach to procurementReference 22, and so concerted action is expected at the regulatory and policy levels. Partnership development for international exchange is already underway with European, Australian and Israeli partners.

Alignment with Roadmap II and Synergies with SPOR: eHealth innovation is an important theme in Roadmap II and with CIHR’s strategic direction to mobilize research for transformation and impact. The focus of IHSPR’s eHealth priority is on the integration of innovative technologies into healthcare delivery to assess value and cost-effectiveness. eHealth is a cross-cutting enabler to achieve all four health and health system priorities of Roadmap II: enhanced patient experience and outcomes through health innovation, health and wellness for Indigenous Peoples, healthier future through prevention, and improved quality of life for persons with chronic conditions.

Potential for Partnering: IHSPR and IA have already established new alignments and applicant partnering for eHealth with the National Research Council Industrial Research Assistance Program (NRC-IRAP), provincial economic development agencies (e.g. Ontario Centres of Excellence, MaRS and Health Technology Exchange-HTX), and health information technology industries (e.g. IBM, McKesson). In addition, provincial health research funders are partnering with CIHR as both applicant and funding partners. Internationally, partnering intent has been expressed by the European Commission’s Ambient Assisted Living Joint Programme, Australia’s Young and Well Cooperative Research Centre, and Israel’s Gertner Institute.

Opportunity for Inter-institutional Collaboration: IHSPR, the Institute of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction (INMHA) and IHDCYH, are already collaborating in the eHealth Innovations Partnership Program on two exemplars: youth and mental health and supporting seniors with complex needs in the community. eHealth solutions are being pioneered by Canadian and other international scientists to support other major CIHR Initiatives such as Personalized MedicineReference 23, Environments and HealthReference 24,25, Pathways to Health Equity for Aboriginal PeoplesReference 26,27, Healthy and Productive Work, and most CIHR Institutes have expressed an interest in advancing eHealth in their own communities.

Expected Impact: In five years Canada will have more health innovation communities (local/regional healthcare environments with leadership comprised of researchers, clinicians, patients, and decision makers) that are integrating eHealth innovations into real-world service delivery. These communities will have a dynamic and growing number of technology partners that are creating and adapting eHealth technologies that reduce the cost of care while increasing access and quality. There will be new international partnerships and Canadian technology innovators will see the uptake of their products and know-how internationally.

Strategic Priority 3: Healthy Aging in the Community

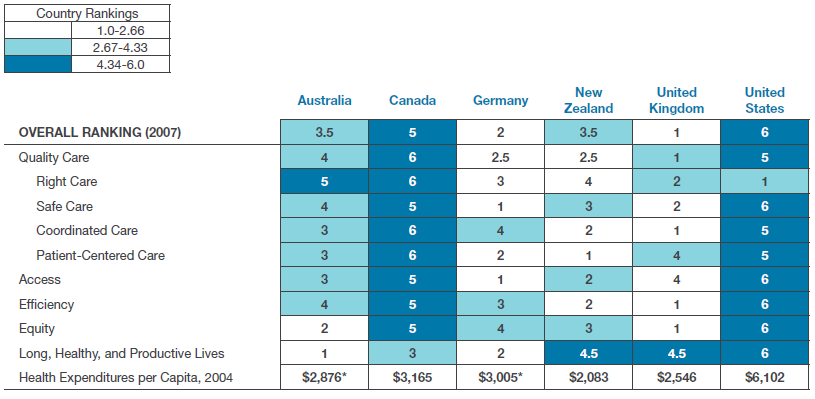

The Canadian healthcare system is not well designed for chronic disease management, particularly the management of multi-morbidity that is most prevalent in the aging population. Canada spends $5446.50 per capita on healthcare, the fifth highest investment in healthcare among OECD countriesReference 2, with the exception of the United States, which has the worst performance in international comparisons (Figure 12).

With the expected demographic shift towards an increasing proportion of older adults (Figure 13), it is paramount that we create communities that can support health aging, including health systems that can more proactively manage multi-morbidity across the continuum of care (Figure 14).

The Gap: Denmark, the Netherlands and Japan are leading in innovative care models to support seniorsReference 28. Integrated systems of care involving community-based primary care and home care are an important feature of these innovative systems.

Figure 12: International Comparisons in Healthcare System Performance: the Commonwealth Fund Survey

Figure 12 long description

| AUS | CAN | GER | NZ | UK | US | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Ranking (2007) | 3.5 | 5 | 2 | 3.5 | 1 | 6 |

| Quality Care | 4 | 6 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1 | 5 |

| Right Care | 5 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

| Safe Care | 4 | 5 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| Coordinated Care | 3 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 5 |

| Patient-Centered Care | 3 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Access | 3 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Efficiency | 4 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 6 |

| Equity | 2 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 6 |

| Long, Healthy, Productive Lives | 1 | 3 | 2 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 6 |

| Health Expenditures/Capita, 2007 | $2,876* | $3,165 | $3,005* | $2,083 | $2,546 | $6,102 |

* 2003 data

Source: Calculated by Commonwealth Fund based on the Commonwealth Fund 2004 International Health Policy Survey, the Commonwealth Fund 2005 International Health Policy Survey of Sicker Adults, the 2006 Commonwealth Fund International Health Policy Survey of Primary Care Physicians, and the Commonwealth Fund Commission on a High Performance Health System National Scorecard.

Figure 13: Historical and Future Expected Age and Sex Distribution in the Canadian PopulationReference 29

Figure 14: The Prevalence of Multi-morbidity by Age

Source: Barnett et al. (2012). Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for healthcare, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. Lancet.Reference 30

However, new models of care have gone beyond the re-configuration of traditional health services to engage communities in providing supportive environments and services for seniors with social innovations such as age-proof dwellings (e.g. Apartments for Life, e.g. Dementia Village), and volunteer networks (Dementia Friends, SOS Wanderers network). Regional health authorities in Canada are just beginning to experiment with new community-based models of care for frail seniorsReference 31-33.

The Objective: Accelerate the experimentation and evaluation of community-based integrated care systems and social innovations to support seniors aging well in the community.

Potential for International Leadership: Canada has the potential to play an increasingly important role in the International community in innovative systems of care for seniors: the Institute of Aging is already part of Europe’s Joint Programming Initiative “More Years, Better Life”; two Canadian Networks of Centres of Excellence have been funded to support innovations in seniors care, AGE-WELL ($36 million) and Technology Evaluation in the Elderly Network (TVN) ($24 million); the eHealth Innovation and Work and Health Initiatives both include thematic focus areas on seniors; and all provincial and territorial Ministries of Health in Canada are focusing on innovations in seniors care.

Alignment with Roadmap II and Synergies with SPOR: SPOR’s PIHCI Network is initially focusing on models to improve care and upstream prevention for high system users with complex needs, of which a large proportion are seniors. This network of learning health systems aims to foster cross-jurisdictional research, and strengthen Canada’s capacity to generate science from the natural experiments that occur on a regular basis in Canada as provinces and territories try different approaches to a common set of challenges. This priority is also well aligned with all four research priority areas of CIHR’s Roadmap II.

Potential for Partnering: In addition to the opportunity for partnership through the More Years, Better Life JPI, we expect that there will be an interest in this area from some of the health charities (e.g. the Alzheimer Society),provincial health research funders, as well as non-traditional partners such as pension funds, developers (aging well communities), and municipalities.

Opportunity for Inter-institutional Collaboration: IA will be fully engaged in operationalizing IHSPR activities related to this objective as a critical collaborator. This collaboration builds on existing productive work with IA. Notably, IHSPR is currently collaboratingwith IA on the eHealth Innovation Initiative. Work in this priority area will also complement the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration in Aging (CCNA) initiative. As most chronic conditions are age-related, we expect there will be interest in this areafrom most other CIHR Institutes.

Expected Impact: In five years we will have synthesized evidence to support policy options and action related to pharmacare, home care and long-term care; and developed and demonstrated evidence to support new models of care for aging well in the community that delay long-term care admission, and reduce avoidable emergency department use and hospitalization.

Strategic Priority 4: Health System Financing, Funding, and Sustainability

With healthcare accounting for almost half of provincial and territorial expenditures, and delivering poor value for comparative investment internationally, it is essential to examine alternative mechanisms of financing and funding and evaluate their comparative effectiveness. In particular, Canada will need to determine how it will finance community-based services that will be essential for effective chronic disease management but that are not covered under the Canada Health Act. Moreover, budget silos for health service sectors along the continuum of care (e.g. hospitals, rehabilitation centres, primary care clinics, home care) act as barriers to innovation and system transformation. Current mechanisms for financing and funding healthcare in Canada provide no incentives for providing better care at lower cost, improving the patient experience, or ensuring the most efficient use of limited resources.

The Gap: Various countries, including Canada, are experimenting with a variety of different approaches to financing and funding healthcare. Private-public financing of services (e.g. drug coverage in Quebec) and infrastructure (e.g. new hospitals in Britain) is being employed as a means of improving access and reducing taxpayer costs, but questions about actual effectiveness, efficiency and convenience still remain unansweredReference 34. There are fears that private-public systems will result in higher healthcare prices and sicker, poorer people being left untreated.

Activity-based funding approaches for hospitals aim to improve efficiencies but results vary widely across studies: some suggest important benefits and some suggest harmful consequencesReference 35. The impact on the quality of care and outcomes of paying practitioners for performance rather than services remains largely uncertain, particularly as it relates to unintended consequencesReference 36. Recent experiments with Accountable Care Organizations (ACO) in the United States are of considerable interest in Canada. Within this model organizations are rewarded for achieving better outcomes and penalized for preventable morbidity, providing an incentive system for front-line innovation in improving health service delivery. The effectiveness of these new models of funding is currently unknown. An emerging approach to improving value for investment in healthcare is through professional engagement and leadership in reducing unnecessary use of resources. Led by the American Board of Internal Medicine, the “Choosing Wisely” movement now encompasses the engagement of virtually all medical societies in the US and Canada as well as Consumer Reports. Choosing Wisely’s impact on reducing preventable morbidity and costs from unnecessary use of drugs, diagnostics and procedures has not yet been evaluated.

The Objective: Evaluate alternative approaches to performance based funding that optimize quality, health outcomes and reduce costs; public-private financing models for providing community-based products and services (e.g. pharmaceutical, home and long-term care, allied health professionals); and new mechanisms for controlling costs through professional leadership and engagement.

Potential for International Leadership: There has been limited empirical investigation of financing and funding systems in healthcare, and few studies that have been able to rigorously assess the impact on outcomes, costs and unintended effects. The Evidence-Informed Health Care Renewal Signature Initiative accelerated the engagement of Canadian health services and policy researchers and policy-makers in evidence synthesis, comparative policy analysis, and policy rounds on issues related to financing, funding and health system sustainability. This network of stakeholders is now poisedtolead on prospective comparative evaluation of natural experiments in financing and funding in provincial and territorial health systems in Canada, and internationally.Moreover, the international network of countries involved in Choosing Wisely is led by a Canadian scientist.

Alignment with Roadmap II and Synergies with SPOR: SPOR’s PIHCI Network along with the SPOR SUPPORT Units will provide the platform for cross-jurisdictional comparisons of different approaches to funding and financing among the provinces and territories, particularly their impact on the complex needs high user group. To increase the speed and volume of scientific through-put, CIHR is partnering with the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) to produce a dynamic cohort of complex needs, high users that will be available to researchers and policy-makers in each jurisdiction to facilitate cross-jurisdictional comparisons of costs and outcomes of different approaches to financing and funding. The manner in which health systems are financed and funded is foundational to all of CIHR’s Health Research Roadmap II priorities.

Potential for Partnering: IHSPR is partnering with CIHI and the US Commonwealth Fund to house the Fund’s International Health Policy survey database in Canada. This will dramatically increase access to the data generated through this annual survey and the capacity of Canadian scientists to conduct international comparative research. The Commonwealth Fund will support Canadian scientists to use its extensive international network of policy-makers and researchers to understand and measure the reasons for international differences in performance. IHSPR will also be partnering with Choosing Wisely Canada, the Canadian think tanks, provincial ministries, and Health Canada to further this priority.

Opportunity for Inter-institutional Collaboration: IHSPR is collaborating with the Institute of Gender and Health (IGH), the Institute of Infection and Immunity (III) and the Institute of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction (INMHA) to engage in professional leadership to improve appropriateness of care. The Institute of Aging (IA) will be interested in financing and funding approaches for drugs, allied professional services, and home care, as this largely affects the well-being of seniors. Similarly, INMHA will be interested in more effective means of funding community-based mental health services that are largely inaccessible except for those with serious mental illness.

Expected Impact: In five years, there will be an increase in cross-jurisdictional and international comparative research that provides evidence about the important attributes of financing and funding that lead to positive and negative effects. Micro-level practice and policy interventions to reduce unnecessary use will have been identified, and scaled up in some jurisdictions to reduce unnecessary adverse effects and costs.

7. Our Outlook: Concluding Remarks

Canada has led the world with its pioneering efforts to create innovative cost-effective healthcare systems. The research agenda for our Institute over the next five years focuses on key elements that will be needed to transition health systems in Canada to deal with the challenge of effective management of an aging population—particularly as it relates to key financing and funding decisions that will either drive or create barriers to innovation and support for a new breed of scientist that can partner with health system stakeholders. IHSPR is one player in this landscape and to achieve success for the country we needed to align our vision and direction. The creation of CHSPRA provides the vehicle and the connectivity to get our “ducks in a row” to deliver on this ambitious mandate. The national SPOR Initiative is providing the foundational infrastructure needed to achieve this objective and is growing capacity to mine the natural experiments in Canadian healthcare.

8. Acknowledgements

The development of IHSPR’s strategic plan was made possible through the commitment and contributions of its Institute Advisory Board members and our diverse community of researchers, knowledge users and partners. Thank you for sharing in our vision for health system transformation in Canada.

We also wish to thank Dr. Terrence Sullivan for his outstanding support and the 25+ organizations that partnered to create the pan-Canadian Vision and Strategy for Health Services and Policy Research. The pan-Canadian Vision and Strategy provided invaluable input to our Institute’s strategic planning process and is closely aligned with the resulting plan.

Appendix 1: Strategic Planning Methodology

| Phase 1 Asset map |

Phase 2 Preliminary strategic analysis |

Phase 3 Pan-Canadian vision and strategy |

Phase 4 Canadian HSPR alliance |

Phase 5 IHSPR strategic plan |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Collected and catalogued data from 27 funders on HSPR investment 2007/8-2011/12 Enhanced with review by Project Regional informants Validated data with leads in each jurisdiction |

Conducted 55+ key informant interviews to gather input Received survey responses from 400+ research and policy/decision makers to further refine input for discussion Analyzed and reviewed with Partners and IHSPR board |

Conducted scan of HSPR priorities in Canada and abroad to inform draft priorities and strategy Hosted April 1 Priorities Forum with 115+ HSPR leaders to refine vision and strategy Hosted Café Scientifique with 115+ members of the public to garner public output Presented draft vision and strategy at CAHSPR conference to 400+ participants Finalized strategy |

Establish an alliance of 20+ HSPR partners committed to working together and with the community to action the panCanadian Vision and Strategy |

Develop new IHSPR strategic plan aligns with pan-Canadian Vision and Strategy and contributes to CIHR’s mandate and validate plan with IHSPR’s Institute Advisory Board |

Appendix 2: Organizations Partnered on IHSPR’s Pan-Canadian Vision & Strategy Initiative

Organizations

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- Canada Foundation for Innovation

- Canada Research Chairs

- Networks of Centres of Excellence of Canada

- Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement (formerly the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation)

- Canadian Breast Cancer Research Alliance

NAPHRO Partners

- Alberta Innovates – Health Solutions

- Fonds de recherché du Québec - Santé

- Manitoba Health Research Council

- Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research - BC

- New Brunswick Health Research Foundation

- Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Applied Health Research

- Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

- Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation

Health Charities

- Heart & Stroke Foundation of Canada

- Canadian Diabetes Association

- Alzheimer Society of Canada

- Parkinson Society Canada

- The Arthritis Society

- Cystic Fibrosis Canada

- Pediatric Oncology Group of Ontario

Canadian Cancer Research Alliance – CCRA

- Canadian Cancer Society

- Alberta Cancer Foundation

- Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation

- Cancer Care Ontario

- Ontario Institute for Cancer Research

Appendix 3: Partner Organizations for Evidence-Informed Healthcare Renewal (EIHR)

- Alberta Innovates – Health Solutions

- Association of Canadian Academic Health Organizations

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health

- Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement

- Canadian Healthcare Association

- Canadian Institute for Health Information

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- Canadian Medical Association

- Canadian Nurses Association

- Canadian Patient Safety Institute

- Health Canada

- Health Council of Canada

- Institute of Health Economics

- Manitoba Health

- Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research

- Newfoundland & Labrador Centre for Applied Health Research

- Northwest Territories Department of Health and Social Services

- Nova Scotia Department of Health and Wellness, and

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

Appendix 4: Roundtable Organizations

- Alberta Innovates - Health Solutions

- Alberta Ministry of Health and Wellness

- Association of Canadian Academic Health Organizations

- British Columbia Ministry of Health

- C.D. Howe Institute

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health

- Canadian Academy of Health Sciences

- Canadian Council of Chief Executives

- Canadian Health Services Research Foundation

- Canadian Healthcare Association

- Canadian Institute for Health Information

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- Canadian Medical Association

- Canadian Nurses Association

- Canadian Patient Safety Institute

- Conference Board of Canada

- Fonds de recherche du Québec – Santé (FRQS)

- Health Action Lobby

- Health Canada

- Health Council of Canada

- Institute for Health Economics

- Institute for Health System Transformation and Sustainability

- Manitoba Health Research Council

- Manitoba Ministry of Health

- Mental Health Commission of Canada

- Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research

- Ministère de Santé et Services Sociaux

- New Brunswick Health Research Foundation

- New Brunswick Ministry of Health

- Newfoundland & Labrador Centre for Applied Health Research

- Newfoundland Ministry of Health and Community Services

- Northwest Territories Ministry of Health and Social Services

- Nova Scotia Health Research Foundation

- Nova Scotia Ministry of Health and Wellness

- Nunavut Ministry of Health and Social Services

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care

- Prince Edward Island Ministry of Health and Wellness

- Saskatchewan Health Research Foundation

- Saskatchewan Ministry of Health

- Trudeau Foundation

- Yukon Ministry of Health and Social Services

- Date modified: